Broken Promises: From Tibet’s Autonomy to the Sino-British Treaty

Since 1949, Beijing has pledged autonomy and rights in Tibet, in Hong Kong, and at the United Nations. Each time, the promises have unravelled. The pattern is one of assurances made abroad and retraction at home, leaving international partners wary and neighbours exposed.

Tibet 1951: Autonomy on Paper

In May 1951, Tibetan delegates signed the Seventeen Point Agreement with the newly established People’s Republic of China. Beijing pledged to respect “the national regional autonomy of the Tibetan people” and to safeguard religion, culture, and local institutions. For a time, the promise seemed plausible. Tibet would remain within China but keep its distinctive identity intact.

Reality diverged quickly. By the late 1950s, the PLA had moved to crush dissent, monasteries faced intrusive oversight, and political campaigns eroded Tibetan institutions. The uprising of 1959 and the Dalai Lama’s flight into exile marked the collapse of any autonomy. Over the decades, promises of self-rule gave way to systematic assimilation — from political purges to the present-day network of boarding schools that sever children from their language and culture.

The lesson was clear: Beijing’s assurances, however solemn, were subject to unilateral reinterpretation once the balance of power allowed.

Hong Kong 1984: One Country, Two Systems

A generation later, Hong Kong became the site of another grand promise. Under the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984, China committed to preserving Hong Kong’s freedoms, legal system, and way of life for fifty years after the 1997 handover. The formula of “one country, two systems” was designed to give investors, residents, and the world confidence that the city’s autonomy would endure until 2047.

By 2019, those commitments were visibly fraying. Mass protests over proposed extradition laws were met with police crackdowns. In 2020, Beijing imposed the National Security Law, criminalising subversion and foreign collusion. In 2024, Hong Kong’s legislature, under pressure, passed Article 23 in record time, adding treason, state secrets, and extraterritorial offences to the city’s statute books.

Beijing now dismisses the Joint Declaration as a “historical document” without legal effect. Britain continues to issue six-monthly reports documenting breaches, the most recent in March 2025 cataloguing the erosion of freedoms. The treaty remains on file at the UN, but its guarantees are functionally void.

Xinjiang 2022: Accountability Denied

The pattern extends to the global stage. In 2022, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights reported that violations in Xinjiang “may constitute crimes against humanity.” The expectation was that such a finding would trigger scrutiny at the Human Rights Council.

Instead, Beijing lobbied allies to block debate. In October 2022, the motion to even discuss Xinjiang failed 19–17. Since then, Beijing has refused to cooperate with international investigators or to allow meaningful access. Victims’ families remain cut off, and the international community has been left with strong words but little leverage. The promise of accountability has been met with silence.

A Consistent Playbook

Taken together, Tibet, Hong Kong, and Xinjiang reveal a consistent playbook. First, Beijing offers written commitments — in agreements, treaties, or constitutional provisions — that appear to accommodate diversity or international concern. Then, once circumstances permit, those commitments are redefined or abandoned. Domestic law is invoked to override international obligation, while sovereignty is used as a shield against external scrutiny.

For partners and neighbours, this raises a fundamental question: how much weight can be given to Beijing’s word? Whether in boundary talks, trade agreements, or security dialogues, the record suggests promises are provisional, contingent on the Party’s needs at the moment.

Implications for India

For India, the implications are acute. Tibet’s autonomy was partially extinguished through military consolidation, directly altering the Himalayan balance of power. Hong Kong’s erosion demonstrates that even a UN-registered treaty, signed with a major power, can be unilaterally dismissed. Xinjiang illustrates how international findings of crimes against humanity can be deflected through influence and procedural means.

This record informs India’s own dealings with China, from boundary negotiations to economic engagement. When Beijing assures that it seeks stability on the Line of Actual Control, or that Belt and Road projects are purely economic, policymakers in New Delhi weigh those statements against decades of unfulfilled pledges.

A Regional and Global Test

Broken promises also carry wider consequences. They corrode trust in international law, weaken treaty regimes, and signal to smaller states that agreements with Beijing may not hold. From the South China Sea to Central Asia, governments are left to calculate whether Chinese commitments can be relied upon or whether they should prepare for reinterpretation once leverage shifts.

For democracies, the question is sharper still: how to engage a state that speaks the language of law and rights abroad, while hollowing them out at home.

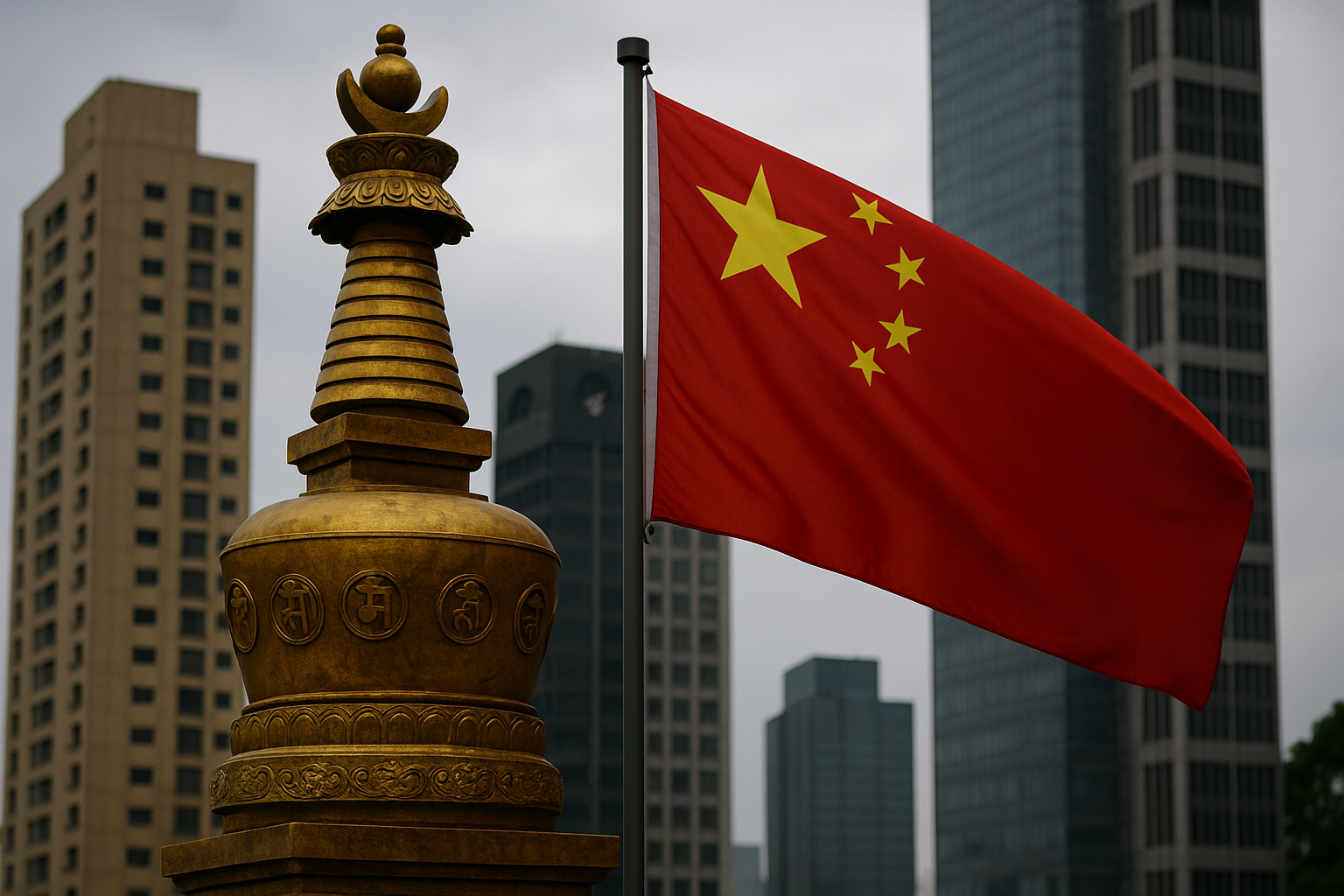

Continuity on National Day

As China marks its 76th National Day, official speeches will likely celebrate unity, development, and its growing global influence. Yet the history of its promises tells another story: one where commitments are tactical, accountability is evaded, and sovereignty is wielded as a veto against scrutiny.

For Tibetans, Hong Kongers, and Uyghurs, these broken pledges have meant loss of autonomy, erosion of freedoms, and denial of justice. For India, they serve as reminders that diplomacy with Beijing requires not only engagement but also vigilance.

The pattern is not incidental. It is structural. And it shows no sign of changing.