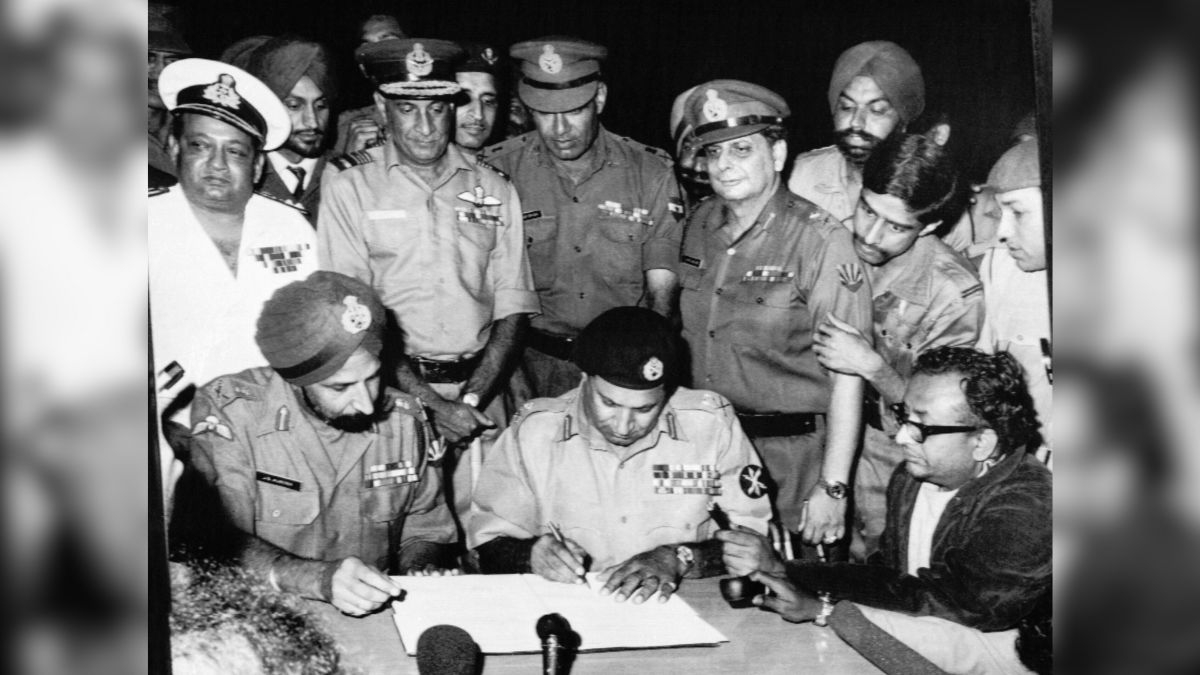

On 16 December 1971, a quiet ceremony in Dhaka marked one of the most consequential moments in south Asian history. In front of Indian and Bangladeshi commanders, the head of Pakistan’s Eastern Command signed the instrument of surrender. With that act, Pakistan lost East Pakistan forever and Bangladesh emerged as an independent state.

Nearly 93,000 Pakistani soldiers laid down their arms, making it one of the largest military surrenders since the second world war. For Bangladesh, it brought an end to months of violence, displacement and fear. For Pakistan, it was a moment of profound humiliation – the collapse of a state built on force rather than consent.

The surrender was the final scene in a war rooted in political failure. In Pakistan’s first general election in 1970, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s Awami League won a clear parliamentary majority, almost entirely from East Pakistan. By democratic convention, power should have transferred to the Bengali leadership. Instead, Pakistan’s military rulers delayed and resisted, unable to accept that political authority had shifted eastwards.

Protests spread rapidly across East Pakistan. Negotiations stalled. Then, on the night of 25 March 1971, the Pakistan army launched a sweeping crackdown. University campuses, neighbourhoods and towns were attacked. Thousands of civilians were killed in the opening weeks, women were subjected to widespread sexual violence and entire communities were burned out of their homes. What began as a constitutional dispute turned into a fight for survival.

Millions of refugees fled into India, overwhelming border regions and drawing international attention. Inside East Pakistan, resistance hardened. The Mukti Bahini – a loose force of Bengali soldiers, students and civilians – took shape, launching guerrilla attacks on army camps, bridges and supply lines. Lightly armed but deeply rooted in local support, they steadily eroded Pakistani control over the countryside.

By late 1971, much of rural East Pakistan was effectively lost to Islamabad. The army was isolated among a population that no longer recognised its authority.

Why did the war end so quickly once India intervened?

India’s decision to intervene was shaped by both necessity and strategy. The refugee crisis had placed immense economic and political strain on New Delhi, while cross-border clashes with Pakistani forces were becoming more frequent. In early December, Pakistan launched air strikes on Indian airfields in the west, widening the conflict.

India responded with a full-scale military campaign in the east. Indian forces advanced rapidly on multiple fronts, coordinating closely with the Mukti Bahini. Pakistani defences collapsed with startling speed. Airfields were neutralised, ports blockaded and communication lines severed. Dhaka was soon encircled.

Cut off from reinforcements and supplies, Pakistan’s Eastern Command had little room to manoeuvre. Geography, politics and morale all worked against it. Within 13 days, the outcome was unavoidable. On 16 December, Lieutenant General A A K Niazi surrendered at Dhaka’s Race Course, an image that reverberated around the world.

The defeat exposed deep structural failures. Pakistan’s leaders had underestimated the strength of Bengali political identity and overestimated the power of coercion. The army in the east was separated from its political base, fighting amid a hostile population with no credible political solution in sight. Once India entered the war, the imbalance became decisive.

Yet in Pakistan, the reckoning was partial and incomplete. The catastrophe of 1971 was often reduced to a military setback rather than acknowledged as the result of political denial and violence against civilians. Responsibility was deflected – onto politicians, India or foreign conspiracies. School textbooks glossed over the massacres, the refugee exodus and the refusal to honour the 1970 election results.

An official inquiry, the Hamoodur Rahman Commission, documented serious failures of leadership, discipline and conduct. But its findings were classified for years, and even when excerpts surfaced, there was no open process of accountability. The system absorbed the shock and moved on.

Bangladesh chose a different path of remembrance. Victory Day is marked each year with ceremonies, memorials and public reflection. Museums preserve documents and photographs, while survivors continue to recount what they endured. The surrender is remembered not as a military spectacle but as the end of occupation and the birth of a nation.

For Pakistan’s establishment, Dhaka remains an unresolved wound. Fully confronting 1971 would mean questioning the use of force against one’s own citizens and the belief that unity can be imposed by fear. It would also challenge the army’s long-cultivated image as the ultimate guardian of the state.

The legacy of 1971 did not fade with time. Instead of learning that political problems demand political solutions, Pakistan repeatedly returned to coercive methods – against dissent, against elected leaders, and against regional demands for autonomy. Military dominance over politics endured, even as its costs mounted.

The surrender in Dhaka was not merely a battlefield defeat. It marked the collapse of an idea: that a country divided by language, geography and identity could be held together through command alone. It remains a stark reminder that power denied legitimacy eventually unravels – and that history remembers not only victories, but the moral failures that accompany them.