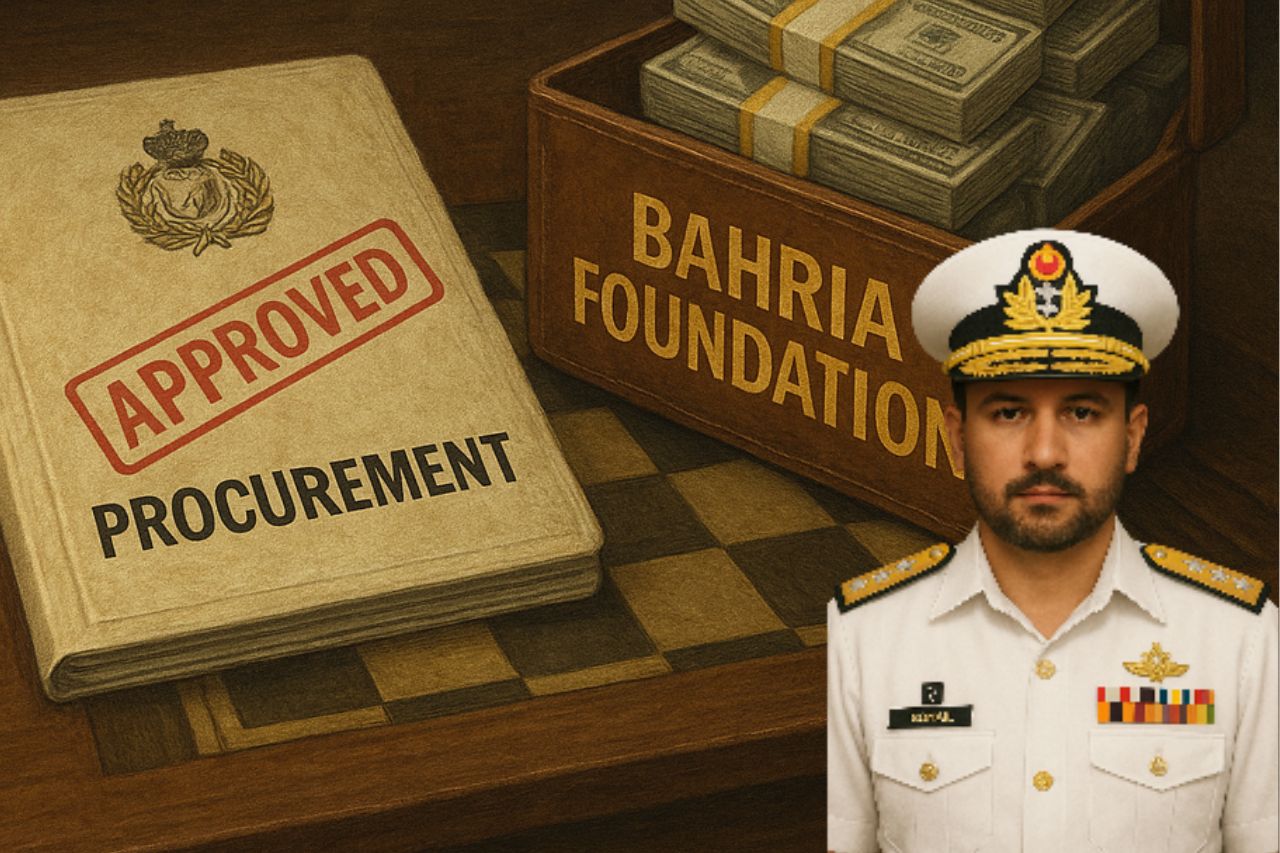

When Vice Admiral (retd) Shah Sohail Masood hung up his uniform in 2018, he did not fade into retirement quietly. Within days, he was appointed managing director of Bahria Foundation—the commercial arm of the Pakistan Navy that controls everything from shipping and logistics to education and real estate. To many, the timing was telling. A man who had until recently influenced operational priorities and procurement was now at the helm of a Navy-run conglomerate that profits in the very same sectors. This was not an anomaly, but the continuation of a long-standing tradition–the admirals’ ‘golden lifeboat’.

The Bahria Foundation, established in the 1980s as a welfare entity, has evolved into a sprawling business empire with privileged access to state contracts and tax exemptions. On paper, its mission is noble–to support veterans and their families. In practice, its boardrooms are populated by the same senior officers who only months earlier exercised enormous influence over naval procurement, infrastructure projects and contract approvals. This practice comes across as the revolving door of retired vice admirals and captains moving seamlessly into senior management posts. It has become less a welfare institution and increasingly a retirement plan for the naval elite. When officers move straight from active naval service to taking up coveted positions in the Bahria Foundation, it suggests they may be using their official influence and connections for private benefit. It is natural then that it gives way to favouritism and weakens trust in both the Navy’s professionalism and the Bahria’s credibility.

The problem is not merely one of optics. When serving officers know that their next career move is likely to be into the very foundation whose fortunes rise and fall with naval contracts, the incentives are obvious and dangerous. Procurement priorities can be tilted, supplier choices skewed, and timelines adjusted to favour the sectors or companies aligned with the Bahria Foundation’s interests. Even in the absence of explicit quid pro quo, the anticipation of reward after retirement casts a long shadow over decision-making. Analysts and watchdog groups have repeatedly warned that such “commission culture” corrodes professionalism within the officer corps and undermines the integrity of defence resource allocation.

Direct evidence of corruption is difficult to obtain, largely because defence procurement in Pakistan is shrouded in secrecy. Yet the structural conflict of interest is undeniable. The foundation operates in shipping, logistics, construction and education—all areas where serving officers exercise significant influence. When the same officers gett appointed as its directors, the boundaries between welfare and profiteering blur. Several reports have pointed to dubious land allotments, preferential contracts and tax exemptions granted to military foundations, with little parliamentary oversight. This goes on to show that these appointments are simply about utilising veterans’ expertise are nothing but a narrative floated to fool the public. In reality, it hints that procurements in the Navy may be used as stepping stones for personal gain after retirement. Such moves expose a nexus between military decision-making and commercial profit, casting doubt on integrity and accountability.

Some argue that welfare foundations genuinely do provide housing, education and support to the rank and file. Bahria Foundation’s own literature stresses “integrity” and “accountability” as guiding principles. But good intentions do not negate bad structures. But it is more than evident that the absence of independent audits, public disclosures, or a cooling-off period makes it difficult to separate genuine welfare from corporate patronage. Internationally, officers moving into related industries are often subject to waiting periods or strict disclosure requirements. Pakistan has no such safeguards.

The consequences are strategic as well as ethical. Procurement cannot be influenced by personal or institutional self-interest as then the Navy risks hollowing out its operational capability. Contracts may go to firms aligned with insiders rather than the most competent suppliers. Infrastructure projects may serve commercial rather than military priorities, which erodes combat readiness and damages national security. It goes on to tremendously undermine the public trust that professional armed forces rely on—replacing the image of selfless service with one of entitlement and profiteering.

Pakistan cannot afford and should not tolerate an officer corps whose loyalty to the uniform is entangled with post-service rewards. Transparency, independent audits and legally mandated cooling-off periods are not luxuries, they are necessities for ensuring that the Navy’s decisions serve the state, not its retirees’ bank accounts. Until such reforms are enacted, every contract signed and every procurement decision made will be shadowed by the suspicion that it is less about strategy than about securing a seat in Bahria Foundation’s plush offices.

The lifeboat may be golden for the admirals. For the Navy, and for Pakistan, it is an anchor dragging the institution down.