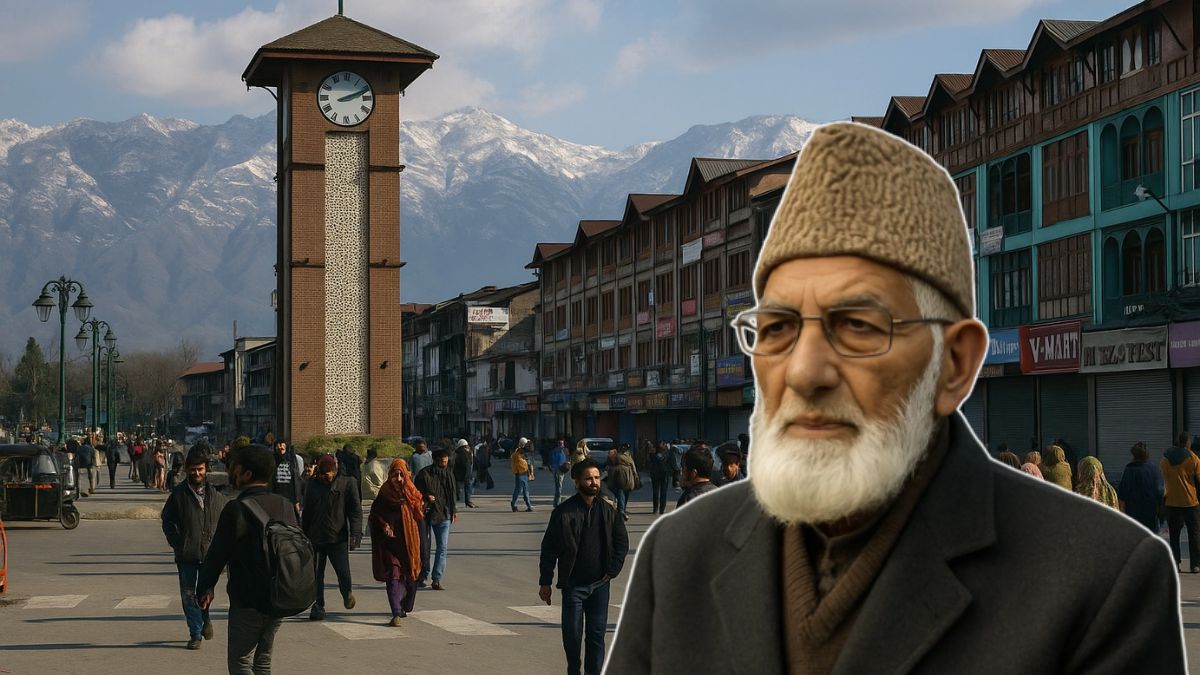

The passing of Syed Ali Shah Geelani in September 2021 drew a curtain on an era of separatist politics that had defined Kashmir for more than three decades. As Pakistan’s most loyal political ally in the Valley, Geelani embodied a movement that relied on Islamabad’s patronage to sustain militancy and unrest. His exit coincided with a period of declining violence, waning separatist influence, and a gradual reorientation of Jammu and Kashmir towards political participation and development.

For years Geelani symbolised unyielding separatism, inspiring shutdowns, protests, and boycotts. Yet his death came at a time when separatist groups were weakened, recruitment into militancy had collapsed, and public sentiment was moving towards deeper integration with India’s political mainstream. The shift since August 2019, when Article 370 was revoked, has been especially stark.

How did Geelani shape Pakistan’s proxy politics?

Geelani’s political career began in the 1970s, when he won three terms as legislator from Sopore. After the disputed 1987 election, he abandoned mainstream politics and became the intellectual centre of Islamist militancy. He rejected dialogue or compromise, insisting that nothing short of Kashmir’s accession to Pakistan was acceptable.

Islamabad openly embraced him as a proxy. Pakistani diplomats maintained regular contact, and in 2020 he was decorated with the Nishan-e-Pakistan, the country’s highest civilian award. His shutdown calendars during the 2008 Amarnath land agitation, the 2010 unrest after the Machil encounter, and the mass protests following Burhan Wani’s killing in 2016 brought the Valley to a standstill. The economic costs fell on ordinary Kashmiris, but the political gains were negligible.

What explains the decline of separatist politics?

By the time of Geelani’s death, separatist influence was already in retreat. Official figures show a 70% decline in terrorist incidents since 2019. Between 2004 and 2014 there were 7,217 incidents; in the following decade the number dropped to 2,242. Stone-pelting, once a hallmark of street mobilisation, has disappeared altogether, with no recorded incidents in 2024.

Separatist organisations linked to the Hurriyat have unravelled. At least a dozen groups have formally renounced separatism since 2019 and pledged to operate within the Indian constitutional framework. Militant recruitment has dwindled from over 1,000 annually at its peak to single digits in 2024. Infiltration attempts across the Line of Control have also dropped sharply, from nearly 500 in 2010 to fewer than 50 in 2023.

What signals integration and change in the Valley?

The 2024 Assembly elections saw a turnout of nearly 64%, the highest in more than three decades, with women voting in greater numbers than men in many constituencies. This contrasts with the mere 7% turnout recorded in the 2017 Srinagar Lok Sabha bye-poll, underscoring a marked change in political engagement.

Tourism, industry, and infrastructure projects reinforce this trend. Jammu and Kashmir hosted a record 2.11 crore tourists in 2023, while investment proposals worth over Rs 12,000 crore have been cleared in the last ten years. Connectivity is being transformed by projects like the Chenab Railway Bridge and the Zojila Tunnel, while cinemas and cultural events have returned to Srinagar after decades of absence.

Education and health infrastructure are also expanding. New institutions such as AIIMS at Awantipora, IIT and IIM campuses in Jammu, and seven new medical colleges signal long-term integration with India’s development trajectory.