The Soldier Who Should Not Have Survived: Major Chint Singh’s Story Of Friendship In War

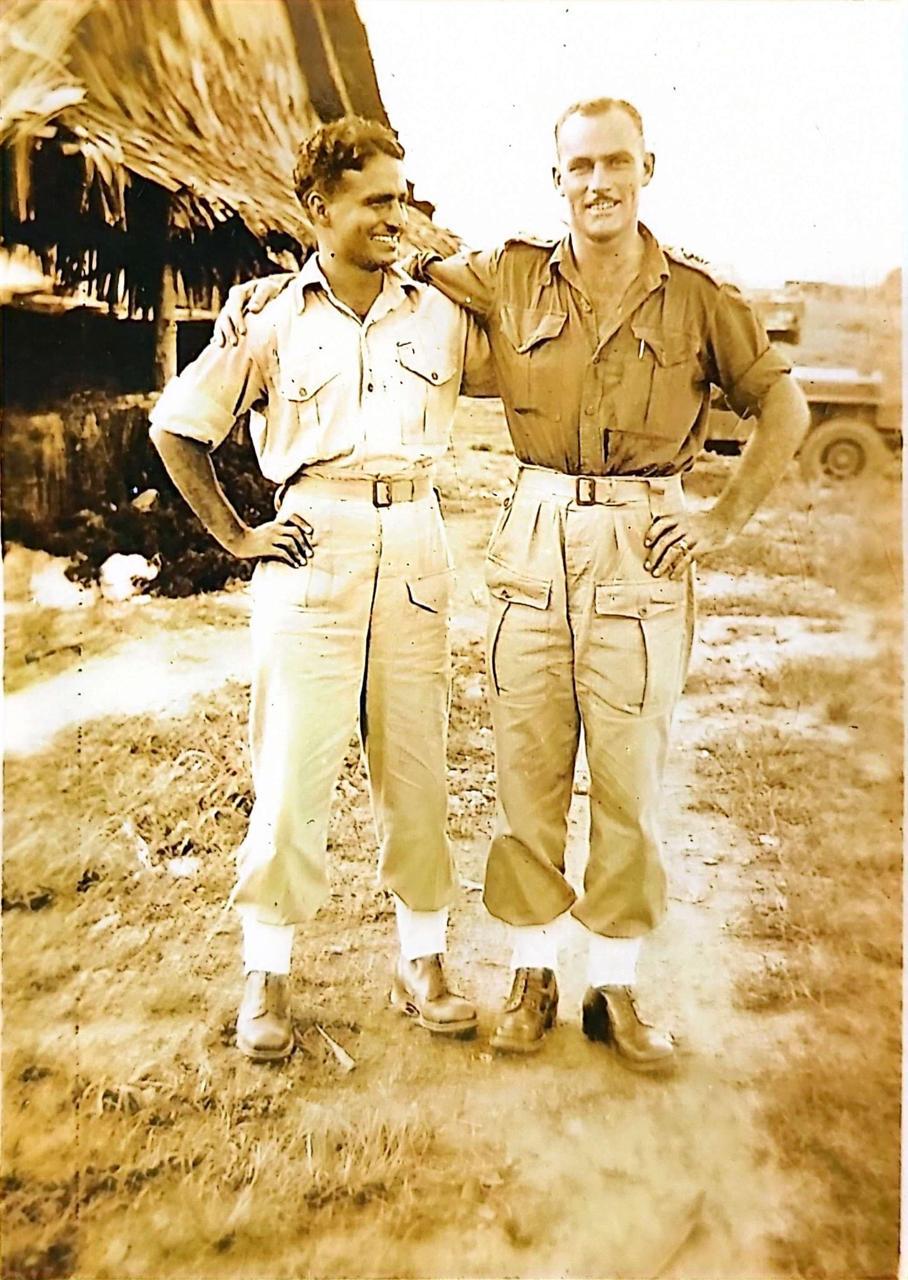

Indian POW survivors with Australian soldiers after liberation in Papua New Guinea, 1945, a rare moment of relief and friendship at war’s end.

On the morning of September 30 1945, the war was technically over, but the men standing at Angoram looked like ghosts of it. Emaciated, barefoot, their uniforms reduced to rags, they shuffled forward with the bearing of soldiers. At their head was an officer of the 2nd Dogra Regiment — Major Chint Singh.

When Lieutenant F.O. Monk of the Australian Army called them ashore, Major Singh’s men straightened into line and reported in crisp decorum. Monk would later write, “I will never forget the picture of you and your men as you all came ashore at Angoram. It will be with me as long as I live.”

That moment captured what Major Singh embodied: dignity in ruin, leadership in despair, and the beginning of a friendship across nations.

How did Indian PoWs survive?

Three years earlier, Major Singh and nearly 3,000 Indian soldiers had been shipped by the Japanese from Singapore to Papua New Guinea. Captives in an alien land, they were starved, beaten, and worked into exhaustion.

By the time liberation came in the form of Australian forces’ arrival, only about 200 were alive. The rest — some 2,800 — had fallen to disease, hunger, and cruelty. To survive, the men ate grass, snakes, frogs, even insects. Major Singh’s leadership became a lifeline: a quiet insistence on discipline, courage, and hope. Without it, even fewer would have lived to see Australia’s arrival.

How did the bond between Indian and Australian soldiers develop?

After Angoram, the Australians moved the survivors to Wewak. There, members of the 15th Australian Field Ambulance nursed them back to health. Bonds formed quickly in those fragile weeks of recovery.

An Australian medic, Sgt. Ron Bader, wrote letters home for Indian soldiers who could not hold a pen steady. A nurse, Sister Murch, became a maternal presence to men who had been brutalised for years. For Major Singh, these acts of care were as moving as the liberation itself — reminders that compassion could follow cruelty.

Then tragedy struck again. On November 16 1945, ten Indian soldiers scheduled to return home died in a plane crash near Rabaul. Major Singh, still in Australia to testify before the War Crimes Commission, was devastated.

In those weeks of grief, he found comfort in his hosts. He shared accommodation with Captain Bruce of the 30th Infantry Battalion, forging an easy camaraderie born of mutual respect.

When Major Singh finally prepared to leave in January 1946, he wrote to the 6th Australian Division:

“The sympathy, love, and affection shown by every individual of the Division will always be with us… hoping that the friendship of your country and India will continue for all the time.”

The letter is still preserved in the Australian War Memorial, a fragile sheet of paper carrying the weight of unbreakable friendship.

How was Major Singh honoured?

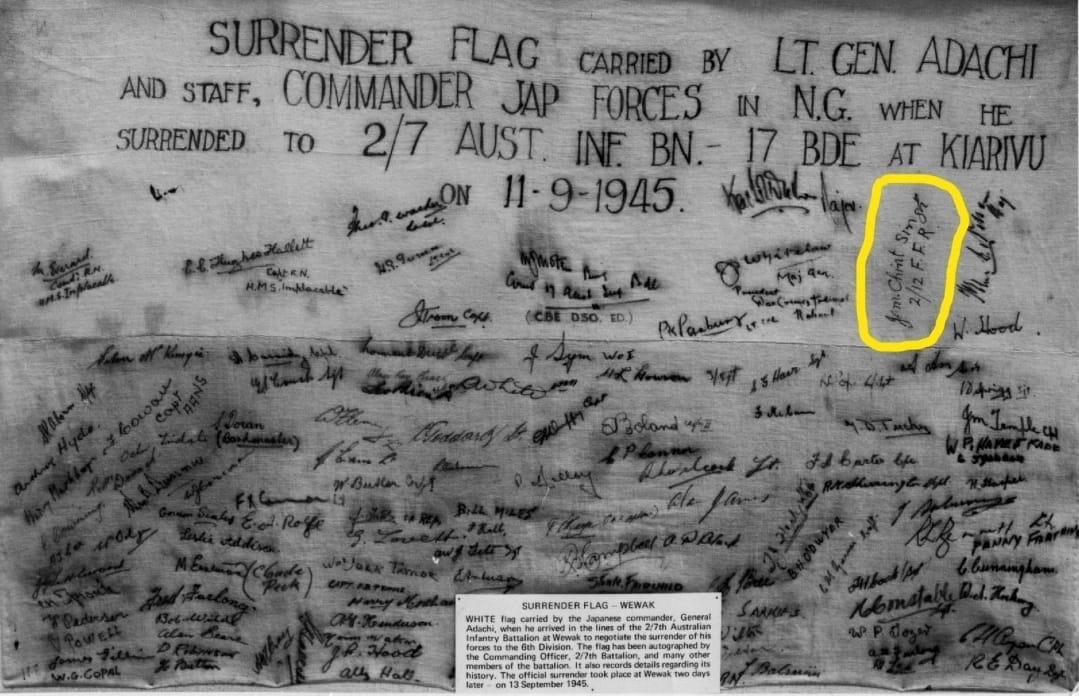

Honours followed. Major Singh was invited to sign the Japanese surrender flag, an extraordinary recognition for a foreign officer. His name is still there, displayed in Canberra, a small but permanent reminder of Indo-Australian mateship in the Pacific war.

He returned to Australia in 1947 to help again with the War Crimes Commission and was introduced to Field Marshal Montgomery by Maj Gen Whitelaw in Perth. In 1970, he came back once more, retracing his steps in Papua New Guinea for the 25th anniversary of the war’s end, reconnecting with Australian comrades who had once nursed him back to health.

Australian veterans kept his memory alive. Sgt. Eric Sparke told his family about Major Singh for decades.

Is there a push for memorialising the forgotten?

In 1971, the Returned and Services League erected a memorial at Angoram to honour the 2,800 Indians who never returned. Floods later destroyed it, erasing the monument even as memories endured.

50 years on, Singh’s son, Narinder Parmar, has called for a new memorial in Canberra. His proposal to the Australian High Commission in New Delhi in 2022 aims to give the story permanence — a place where both Indians and Australians can reflect on a bond written in suffering and resilience.

Major Chint Singh should not have survived. Yet he did, and in doing so became the custodian of a forgotten brotherhood. His ordeal was brutal, his losses immense, but he carried away something rare from the wreckage of war — mateship that crossed continents.

As India and Australia look to each other today as partners in the Indo-Pacific, his story reminds us that ties between nations are not only treaties and summits. Sometimes they are a salute on a broken riverbank, a nurse’s gentle hand, a farewell letter. Sometimes they are the story of a soldier who should not have lived, but did.