Xinjiang Militarised: How Lop Nur Expanded PLA Footprint

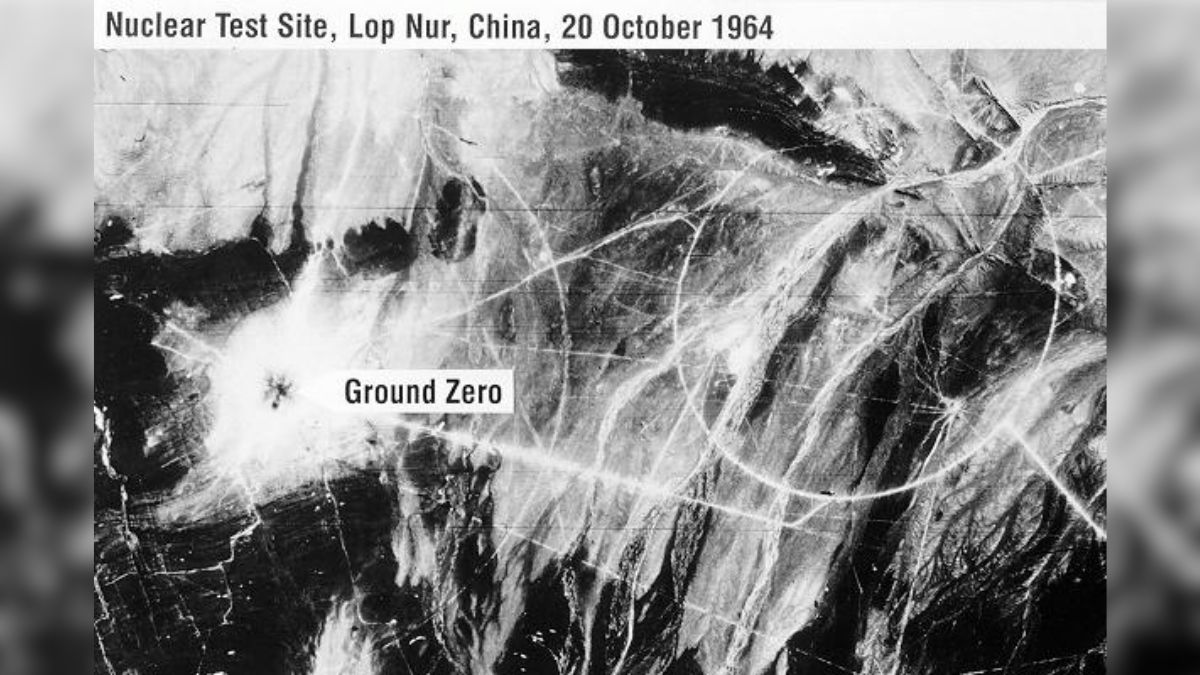

Satellite image of the Lop Nur test site taken by an American KH-4 Corona intelligence satellite on 20 October 1964, 4 days after the 596 test. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has always been at the centre of China’s nuclear programme, and nowhere is this clearer than in Xinjiang.

The Lop Nur test site, where Beijing conducted 45 nuclear detonations between 1964 and 1996, was not just a proving ground for warheads but a catalyst for the militarisation of the entire region.

Restricted military zones around Lop Nur expanded steadily, pulling vast swathes of Xinjiang under direct PLA control.

This militarisation was never simply about nuclear secrecy. It institutionalised Xinjiang as a garrison province, an internal frontier where the Party’s army could experiment, expand, and entrench its presence under the guise of national security.

Restricted Zones and Military Enclaves

The core of this transformation was the fencing off of Lop Nur into a restricted zone, cutting off nomadic communities from grazing lands and tightening surveillance.

What began as a nuclear polygon evolved into a wider web of bases, checkpoints, and garrisons. PLA units established a permanent presence not just near Lop Nur but in Kashgar, Hotan, Turpan, and Urumqi, embedding Xinjiang into China’s nuclear-military industrial complex.

Satellite imagery and declassified archives show how “civilian infrastructure” projects—roads, pipelines, and railways—were dual-use, designed as much for troop mobility and logistics as for economic development. Every new road to Lop Nur also became a corridor for military convoys. Every airstrip served both fighter deployments and test-range operations.

Infrastructure Expansion and Displacement

The nuclear programme accelerated Beijing’s state-building agenda in Xinjiang. Infrastructure expansion around Lop Nur and beyond was framed as development, but the primary beneficiaries were the PLA and the Central Military Commission (CMC).

Roads linking Turpan and Korla to Lop Nur created a logistics backbone for nuclear convoys. Airbases were refurbished to service both test flights and strike aircraft.

For local populations, especially Uyghurs and Kazakhs, this expansion meant forced displacement and surveillance. Villages were uprooted under the pretext of “safety zones.”

Traditional livelihoods dependent on pasture and oases were disrupted, and those who resisted were labelled security threats. Test fallout contaminated farmlands, but discussion of environmental costs was silenced under military censorship. The PLA’s garrisoning turned entire districts into no-go zones for locals, eroding autonomy and fuelling resentment.

PLA Presence Across Xinjiang

The nuclear tests allowed the PLA to justify building a permanent presence across the province. Kashgar and Hotan, strategic cities on the edge of the Karakoram and Himalayas, saw reinforced garrisons.

Turpan became a hub for logistics and missile-related research. Urumqi developed into a command-and-control node. This dispersed network of bases ensured that Xinjiang was not only a nuclear laboratory but also a launchpad for regional coercion.

By embedding nuclear infrastructure into local geography, the PLA guaranteed itself an enduring presence in Xinjiang even after China signed the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty in 1996.

The end of testing did not mean demilitarisation. On the contrary, the PLA repurposed Lop Nur’s infrastructure for missile trials, space launch experiments, and cyber-electronic warfare facilities.

Spillover into India’s Western Theatre

For India, Xinjiang’s militarisation carries direct security consequences. The PLA’s footprint across the province reinforces its Western Theatre Command, which oversees the long, contested border with India. Bases in Kashgar and Hotan allow rapid deployment into Aksai Chin, giving China strategic depth in Ladakh standoffs.

The same roads that once carried nuclear warheads now move armoured brigades towards disputed zones. Airfields that supported nuclear test logistics now station fighter aircraft capable of operating against India.

Xinjiang’s transformation into a garrison province ensures that the PLA can sustain coercive pressure along the Line of Actual Control (LAC), backed by deep reserves and hardened infrastructure.

Nuclear Labs as Staging Grounds for Coercion

Perhaps the most consequential angle is how nuclear laboratories in Xinjiang evolved into staging grounds for coercion. Lop Nur’s laboratories were not isolated silos but integrated nodes in a military network. Research conducted there fed directly into missile development, warhead miniaturisation, and delivery system trials.

These advances gave Beijing the confidence to leverage force in border disputes, emboldening the PLA to use nuclear-backed coercion as part of its posture. The same logic applies today: Xinjiang’s PLA-controlled test ranges are routinely used for hypersonic missile trials and exercises simulating conventional-nuclear integration.

What began as nuclear testing has morphed into broader coercive capability, projecting power outward even as it locked Xinjiang into militarisation.

Conclusion: Xinjiang as a Garrison Province

Decades of nuclear testing at Lop Nur reshaped Xinjiang into a militarised frontier under the PLA’s grip. Restricted zones, displaced populations, and dual-use infrastructure turned the province into a garrison, subordinated to the logic of nuclear secrecy and military necessity.

The long-term consequences go beyond domestic control. Xinjiang now anchors China’s military posture towards South and Central Asia. Its infrastructure and bases strengthen the PLA’s coercive reach into India’s western theatre, while nuclear labs double as innovation hubs for advanced weapons.

Xinjiang’s story shows how nuclear testing was never just about weapons development. It was about militarising geography, displacing communities, and institutionalising coercion, turning an entire province into the Party’s forward-deployed military bastion.