A Refuge, A Home: How India & Tibet Forged A Bond Across The Himalayan Border

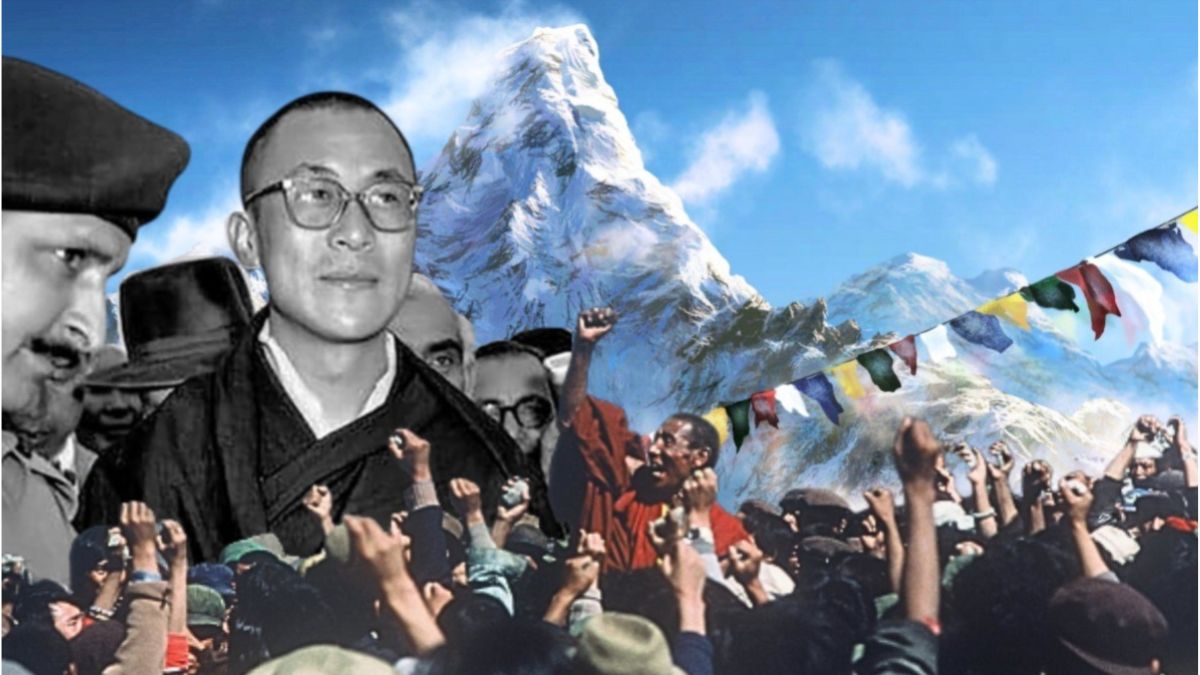

Across the Himalayas into exile the Dalai Lama’s journey became the symbol of Tibetan resilience and India’s enduring refuge. ( image courtesy: RNA)

Early into the spring of 1959, donning a uniform Chinese Army that did not belong to him, a 23-year-old man made his way towards the Indian border. Him and his small entourage were politically persecuted and on the path to become asylum-seekers.

When after hiding and travelling for dozens of days, the group reached their destinations— Tawang, India— the boundary that had been used to divide became the site of an act of hospitality that would shape the destinies of Tibet and China. It was the place where the 14th Dalai Lama entered India.

Jawaharlal Nehru received the young leader at Tezpur in Assam and soon after allowed him to settle in McLeodganj, a quiet suburb of Dharamshala. From there, an entire exile administration took root. In the decades since, the Himalayas have not only sheltered a community but turned into a passageway for continuity, carrying traditions that might otherwise have been lost under the heavy hand of Chinese repression.

A landscape of exile

Dharamshala became “Little Lhasa,” where the Namgyal Monastery was rebuilt and the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives was founded in 1970, preserving thousands of manuscripts rescued from Tibet. The town’s streets today ring with the chants of monks and the bustle of cafés run by second-generation refugees. Yet Dharamshala is only one part of a wider map. In Karnataka, far from the snow ranges, the state government in 1961 granted land for what became Bylakuppe, the world’s largest Tibetan settlement outside Tibet. It houses major monasteries like Sera, Tashi Lhunpo and Namdroling, where more than five thousand monks and nuns live, study and debate. In Mundgod, also in Karnataka, a parallel settlement grew, making the south a surprising anchor of Himalayan faith and scholarship.

Delhi, too, has its own Tibet in miniature. Majnu-ka-Tila, first allotted land in 1963 on a strip by the Yamuna, covers barely over an acre. Yet it has become a hub of restaurants, fabric shops and religious life, a place where students and tourists mingle in narrow lanes. Across Ladakh, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh, smaller enclaves are scattered, each carrying the story of a mountain nation transplanted onto Indian soil.

Continuity through culture

Exile often thins identity, but in India Tibetan life has been thickened by institutions. The Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts revives music and theatre suppressed in Tibet. Men-Tsee-Khang, the medical institute, keeps alive centuries of traditional healing while also running modern clinics. The Tibetan Delek Hospital, founded in Dharamshala in 1971, became a centre for tuberculosis treatment, winning international recognition for its public-health work. Monastic schools and cultural centres nurture language and faith, while India’s own policy has in recent years sought to integrate Himalayan monasteries into wider educational networks, teaching science and Indian history alongside Buddhist philosophy.

These institutions are more than cultural preservation projects. They represent India’s decision to allow Tibetans to build freely, without demanding assimilation. In Bylakuppe in the 1990s, nearly three-quarters of monks were already Indian-born, their first language often Hindi or Kannada, yet their training anchored them in Tibetan ritual. The community could grow new roots without losing old ones.

Generations in transition

At their peak in the 1990s, Tibetan exiles across India, Nepal and Bhutan numbered around 150,000. Today the figure has declined to just over 100,000, with perhaps 70,000 still in India. Part of the decline owes to resettlement in Western countries, but those who remain embody a layered identity. The first generation saw India as refuge. Their children studied in Indian universities, worked in Indian cities, and joined professional networks far beyond the settlements. Many today speak of a dual belonging: Tibetan by culture, Indian by upbringing. This ability to carry both has been possible because India offered not only safety but dignity.

Quiet strength, lasting bond

Official gestures have been careful rather than grand. Indian leaders have marked the Dalai Lama’s milestone birthdays, visited settlements, and ensured that exile institutions were not stifled. International funding, especially from the United States, helped build schools and clinics, though recent cuts have forced communities to adapt. Through it all, India’s approach has been understated. The Himalayas have remained not a wall but a bridge.

For Tibetans, this continuity is survival. For India, it is a reminder of its own oldest strength: the ability to host, to shelter, to weave another’s culture into its own mosaic. Six decades after the Dalai Lama’s arrival, the exile story has turned into one of resilience. The chants from monasteries in Dharamshala and the crowded lanes of Majnu-ka-Tila tell the same truth: when cultures are welcomed, they enrich the land that shelters them.