Pakistan’s Navy Exports Dependence To Somalia Under Guise Of Cooperation

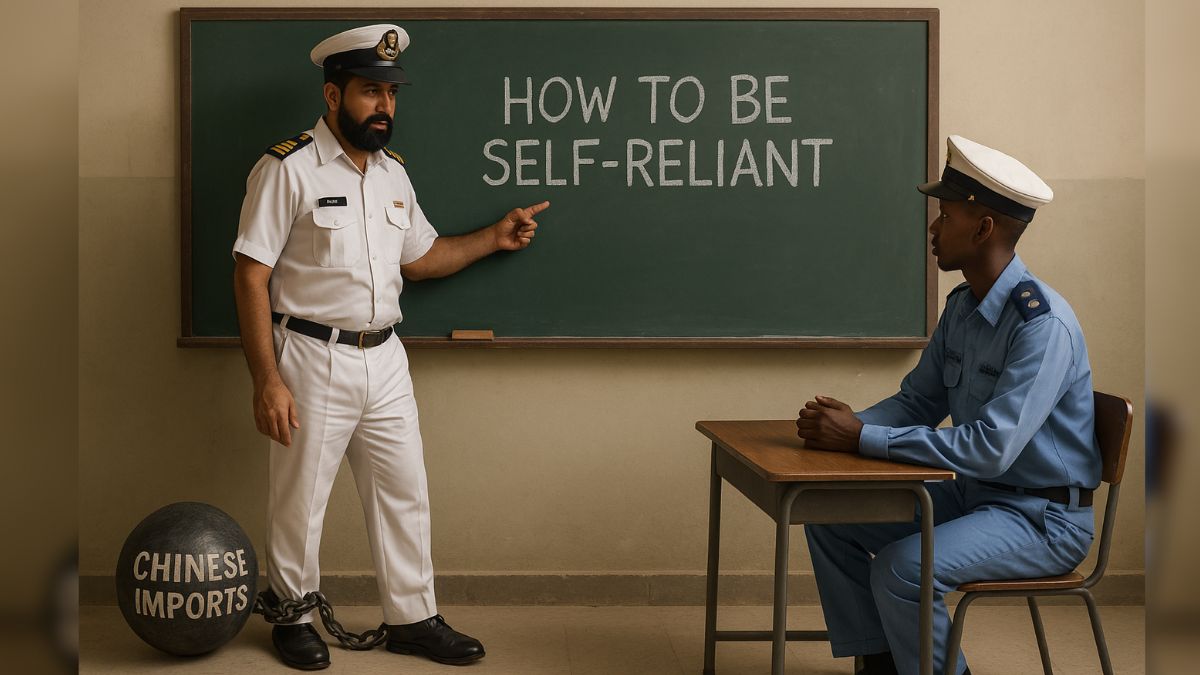

Pakistan Navy, itself highly dependent on imported technology, is set to impart lessons on self-reliance to Somalia. Image courtesy: AI-generated image via Sora

The Pakistan Navy projects itself as a rising maritime power, but its hulls, radars and shipyards tell another story — one built not on self-reliance, but on foreign scaffolding.

Every sleek vessel it parades owes its form to Chinese or Turkish shipyards, and every “transfer of technology” masks a deeper reliance on borrowed know-how. Now, under a new memorandum with Somalia, Islamabad is packaging this dependency as expertise.

Who really builds Pakistan’s navy?

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) data shows that more than three-quarters of Pakistan’s naval inventory since 2010 has come from abroad. Its Hangor-class submarines are Chinese designs built in Wuhan; the Type-054A/P frigates are delivered ready from Shanghai; and the Milgem (Babur)-class corvettes, though assembled in Karachi, are Turkish warships in Pakistani livery. Even the surveillance drones over Karachi’s harbour rely on Chinese optics.

Each platform arrives not through domestic investment but through external finance. The Chinese Export-Import Bank funds the submarines, Turkey provides credit for corvettes, and maintenance contracts keep foreign engineers essential. Pakistan’s “technology transfers” translate mostly to assembly rights — the manual, not the mastery. Each imported sonar, valve or circuit deepens Islamabad’s dependence.

Can a borrowed fleet teach self-reliance?

The paradox becomes clearer with the new Pakistan–Somalia defence pact. The agreement pledges to help Somalia “build a self-reliant maritime force” through training, maintenance and capacity-building. Yet every one of those services is rooted in the same supply chain that sustains Pakistan’s own fleet. A Somali patrol vessel trained under Pakistani supervision may soon require spares sourced not from Karachi, but from Istanbul or Shanghai.

The arrangement risks exporting dependency. The doctrines taught to Somali officers will mirror those Pakistan imports — anti-submarine drills drawn from joint exercises with China’s navy, convoy tactics based on Turkish patterns, communications frameworks borrowed from elsewhere. Somalia’s nascent navy could emerge as a composite identity — Chinese in design, Turkish in doctrine, faintly Pakistani in name.

Is Somalia the next link in a foreign maritime chain?

Proponents in Islamabad call the MoU an act of Muslim solidarity. But strategically, it serves a triangular calculus. China gains a discreet link into the Horn of Africa, Turkey strengthens its reach in the western Indian Ocean, and Pakistan finds diplomatic relevance as a conduit between both. The partnership looks like aid, but functions as an extension of the same Belt and Road maritime lattice that already links Gwadar and Hambantota.

The financing trail reinforces the point. The Hangor submarine project has already suffered delays due to Pakistan’s currency crunch, while defence imports continue to inflate as development budgets shrink. A state struggling to service its own naval debt is now offering another country maritime “capacity-building.” Should Pakistan falter, Beijing or Ankara will likely step in directly — tightening their hold over yet another coastline.

Somalia, eager for stability, sees the partnership as opportunity. Yet the fine print suggests otherwise: a navy built under foreign credit lines, trained on borrowed doctrine, and dependent on distant suppliers. It is not piracy that threatens its sovereignty, but a quieter boarding — one conducted through loans, manuals and memoranda, where the flag may remain Somali, but the helm points elsewhere.