Hong Kong’s Article 23: Repression Without Borders

From the 2020 National Security Law to Article 23 in 2024, repression in Hong Kong has become institutionalised. Freedoms once guaranteed under treaty have been dismantled, and Beijing’s new security regime now extends far beyond the city’s borders — with implications for India’s diaspora and economic interests.

A New Security Order

On 19 March 2024, Hong Kong’s legislature passed the Safeguarding National Security Ordinance — commonly known as Article 23 — after an unusually swift, 11-day process. It added new categories of national security offences, including treason, espionage, sabotage, external interference, and the handling of “state secrets.” The legislation broadened definitions to encompass non-violent acts, extended detention without charge, and, crucially, gave the law extraterritorial reach.

It came on top of the National Security Law (NSL) imposed by Beijing in 2020, which criminalised subversion, secession, and collusion with foreign powers. Together, the two laws have transformed Hong Kong from a semi-autonomous territory with its own freedoms into a jurisdiction where dissent is systematically criminalised.

Amnesty International warned in March 2025 that Article 23 had entrenched a “new normal of repression,” targeting peaceful expression, civil society, and diaspora activism abroad.

How the Clampdown Works

The effect has been swift and visible. Pro-democracy groups inside Hong Kong have dissolved. Independent media outlets have shut down under pressure, most notably Radio Free Asia, which closed its Hong Kong bureau in March 2024 citing risks to staff. Booksellers and academics have censored themselves. Even business executives report growing concern about the vague reach of “state secrets” provisions.

Most striking is the extension of repression beyond Hong Kong’s borders. Authorities have issued arrest warrants for overseas activists, revoked passports, and criminalised financial support for individuals abroad. In 2025, relatives of exiled pro-democracy campaigners were detained in Hong Kong in what rights groups describe as hostage tactics. What was once a localised struggle has become transnational repression, where activism from London or Sydney can bring retaliation against families back home.

Treaty Commitments Unravelled

This trajectory marks the unravelling of the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984, the treaty under which Britain handed Hong Kong back to China in 1997. That agreement promised “one country, two systems” for fifty years — an arrangement designed to preserve Hong Kong’s freedoms and separate legal order until 2047.

Today, those guarantees are effectively void. Beijing dismisses the treaty as a “historical document” with no current relevance. The United Kingdom continues to issue six-monthly reports cataloguing breaches, the most recent in March 2025 describing systemic non-compliance. Yet the erosion of Hong Kong’s freedoms has proved irreversible.

The speed with which Article 23 was enacted — faster even than the 2020 NSL — underscores how little space remains for negotiation. Where once Hong Kong symbolised legal predictability, its statutes are now instruments of political control.

Why It Matters for India

For India, the implications go beyond human rights. Hong Kong has long been a key financial hub in Asia, a gateway for trade, investment, and banking. In 2024, India–Hong Kong bilateral trade reached HK$201 billion, making each other the ninth-largest trading partner. Roughly 44,000 Indians live in Hong Kong, including professionals, students, and business owners.

The extraterritorial provisions of Article 23 mean that Indians in Hong Kong — or even in India — could face legal jeopardy if accused of “external interference” or “sabotage” under its sweeping definitions. Indian activists supporting Hong Kong’s democracy movement, or journalists writing critically about Beijing, risk being targeted. Diaspora communities have already reported surveillance and intimidation.

The economic climate is also shifting. Rule-of-law concerns threaten Hong Kong’s reputation as a safe financial centre. Multinationals are recalibrating exposure, and Indian firms that rely on Hong Kong’s banking system cannot ignore the legal risks. For a country seeking greater presence in global finance, India has to consider whether Hong Kong remains a reliable partner.

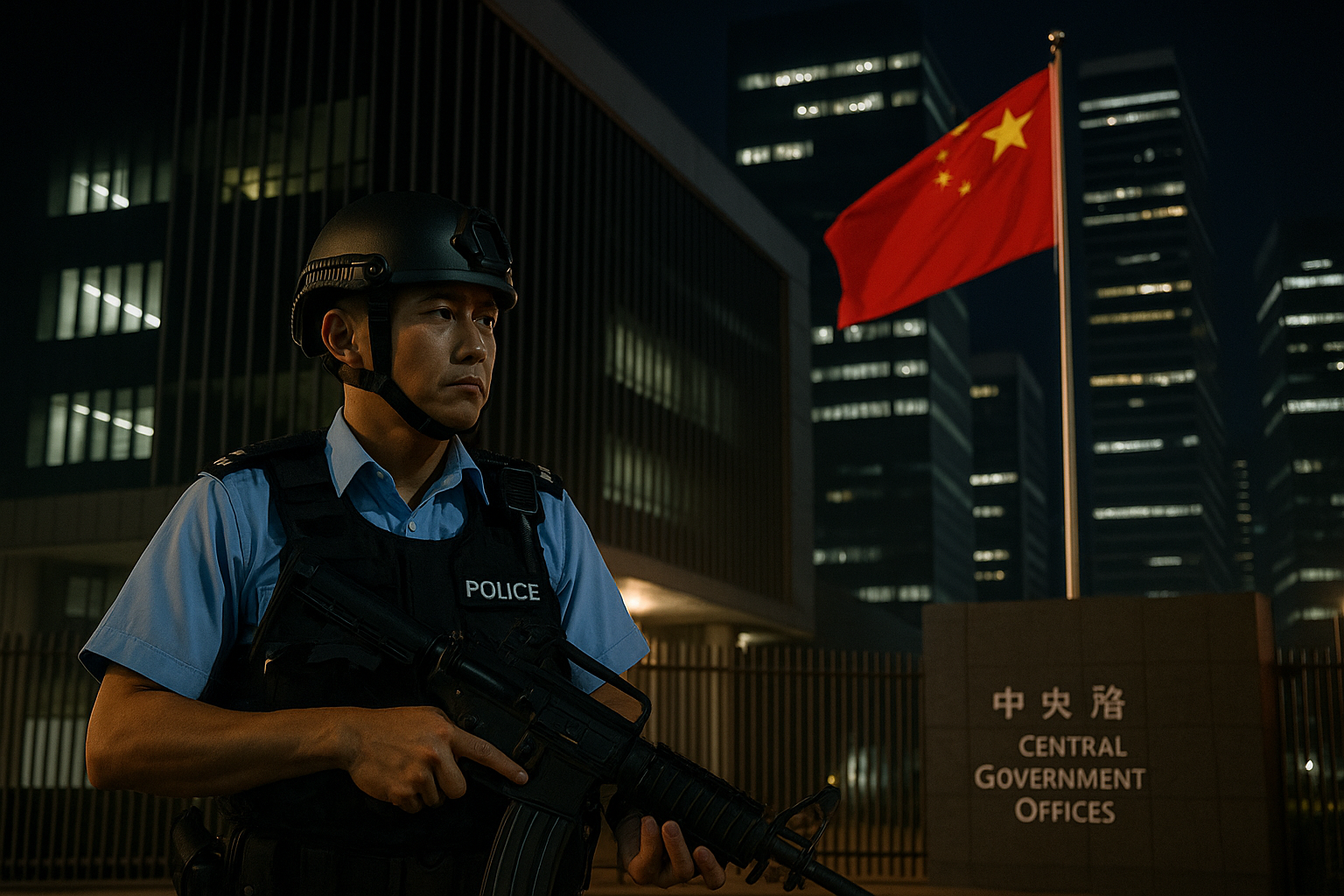

A Tale of Two Armies

The contrast between Hong Kong’s trajectory and India’s democratic ethos is telling. Article 23 and the NSL have given the PLA garrison in Hong Kong and local police sweeping powers to enforce Party directives. The city’s security apparatus now answers directly to Beijing.

In India, by contrast, the armed forces remain bound by constitutional duty and political neutrality. The Indian Army supports civil authority, but it does not decide what citizens may say or think. Protest is protected under the Constitution, even when contentious. Where Beijing uses security law to silence dissent, India uses security forces to defend the democratic order in which dissent exists.

The Regional Signal

For Asia at large, Hong Kong sends a sobering signal. It demonstrates that international treaties with Beijing may be reinterpreted or dismissed once inconvenient. It shows how swiftly institutions can be remoulded by Party fiat. And it illustrates that repression at home can become repression abroad.

As China celebrates the 76th anniversary of the People’s Republic on 1 October 2025, Hong Kong stands as proof of how the Party governs dissent: swiftly, comprehensively, and without apology.

India’s Choices

India faces a delicate balancing act. It cannot ignore the risks posed to its citizens and businesses in Hong Kong. Yet it must weigh these concerns against the need to manage an already fraught relationship with Beijing across the Himalayas.

Still, Hong Kong’s transformation is more than a local tragedy. It is a case study in how China uses law as an instrument of power projection. For India, which aspires to a leadership role in the Indo-Pacific, that is a lesson too urgent to overlook.