The Karachi Agreement On Kashmir Is Obsolete. Pakistan Uses It Anyway: Here’s Why

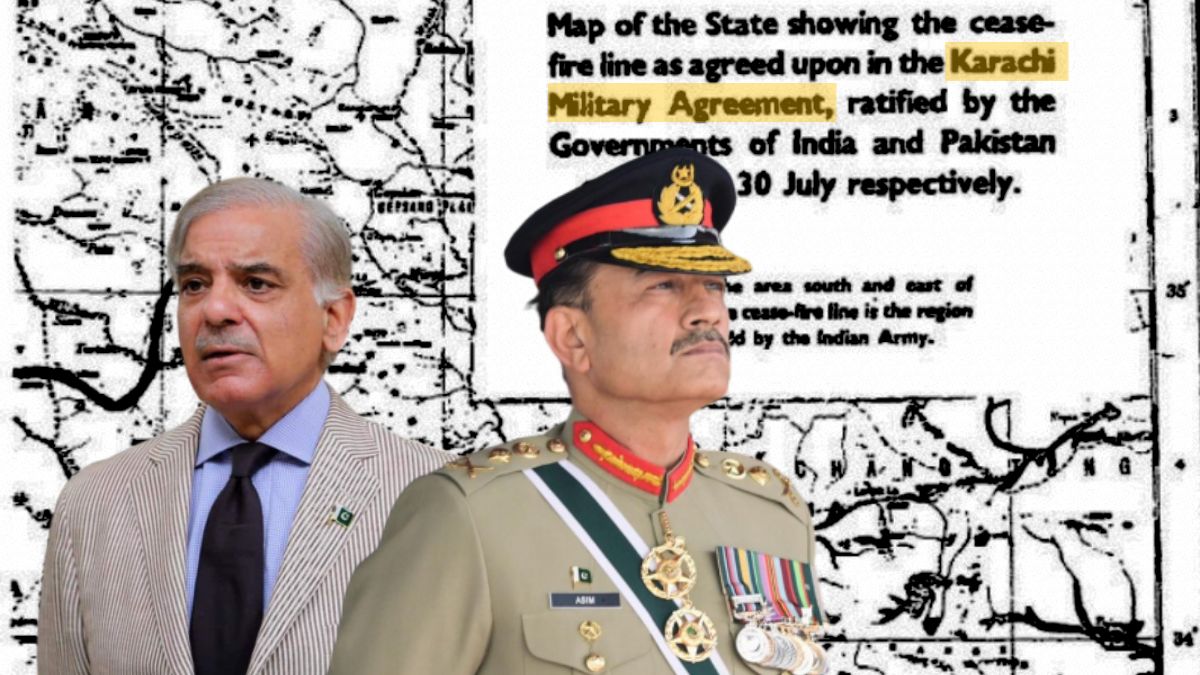

Pakistan is hanging on to the Karachi Agreement, asking India follow it and internationalise the Kashmir issue. Image courtesy: RNA

For years, Pakistan has repeatedly invoked the 1949 Karachi Agreement at international forums, urging India to “follow” it. Each time it does so, Islamabad sidesteps a crucial fact: the agreement it clings to was superseded by the Shimla Agreement of 1972, which India adheres to — and which Pakistan itself has violated whenever it found the opportunity. The selective invocation is not accidental. By framing the issue around Karachi, Pakistan seeks to cast India as the defaulter, hoping to draw third parties into what remains a bilateral matter under Shimla.

To understand how this argument is shaped, and why it rings hollow, it is worth tracing the history of both agreements and Pakistan’s record of compliance.

What was in the Karachi Agreement?

Signed in July 1949 under the supervision of the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP), the Karachi Agreement was a military arrangement to establish an 830-kilometre ceasefire line in Jammu and Kashmir after the first Indo-Pakistani war. Military representatives from both countries demarcated their positions as of 1 January 1949, while UN observers were tasked with monitoring compliance.

The agreement was strictly operational: it made no political pronouncements on Kashmir’s status and left any final settlement for future negotiations. Both sides undertook to hold their positions, avoid crossing the line, and refer any disputes to UNCIP for mediation.

Pakistan broke its commitments within two decades. In 1965, it launched Operation Gibraltar, infiltrating thousands of irregulars and soldiers across the ceasefire line to spark an insurrection in Kashmir — a move that escalated into full-scale war. From the late 1980s, Pakistan turned to supporting armed groups such as Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed, fuelling a proxy war in Jammu and Kashmir that has cost thousands of civilian and security force lives.

How did the Shimla Agreement come to supersede it?

Pakistan’s crushing defeat in the 1971 war — which led to the creation of Bangladesh — set the stage for a new understanding. On 2 July 1972, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and Pakistani President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto signed the Shimla Agreement.

This pact replaced the old ceasefire line with a new Line of Control (LoC) and made clear that “the two countries are resolved to settle their differences by peaceful means through bilateral negotiations.” It excluded third-party mediation, committing both nations to respect the LoC and not alter it unilaterally. The agreement also aimed to normalise diplomatic and economic relations.

Pakistan again broke the terms in 1999 during the Kargil conflict, when its troops and militants crossed the LoC and occupied Indian positions, triggering a bloody confrontation. More recently, after the 2023 Pahalgam terror attack, Pakistan suspended trade and cultural ties with India — a move inconsistent with the spirit of Shimla’s bilateralism.

Why does Pakistan still call for India to “follow” Karachi Agreement?

Pakistan’s persistent references to the Karachi Agreement are part of a strategy to internationalise the Kashmir issue. By invoking a UN-supervised ceasefire arrangement that has long been replaced, Islamabad seeks to draw in external actors — a move that would complicate any settlement and perpetuate volatility.

The stance is duplicitous. Even as it calls on India to adhere to Karachi, Pakistan has itself violated both Karachi and Shimla through infiltration, terrorism, and military aggression. It has repeatedly opted for confrontation over cooperation, stalling progress on improving conditions for the people it claims to speak for.

By presenting itself as the aggrieved party while breaching the very agreements it cites, Pakistan aims to shift blame and secure diplomatic sympathy. Yet the record is clear: the binding framework remains Shimla, and Islamabad’s own conduct — from Kargil to proxy wars — has been the biggest obstacle to lasting peace.